After graduating from Montana State University (MSU; Bozeman) and applying his degree in mechanical engineering technology to four years’ employment at Jungst Scientific and Blackhawk Industries, Matt McCune started his design, development, and prototype business with a “once in a lifetime” opportunity, a huge project contracted by a large company. Working with SolidWorks CAD software in his living room, he quickly encountered his first hurdle, making parts. Because other prototyping methods were incapable of making intricate working parts with close tolerances, machining would be required.

Machine shops in the area balked, pronouncing the project impossible, or quoting it as a prohibitively expensive experiment without fixed price or guarantee of success. McCune found himself in a time squeeze, which was exacerbated by his inability to persuade the customer to purchase a mill, but alleviated by the customer’s agreement to purchase parts at a fixed price. Leveraging his home equity, McCune purchased a Haas Super Mini Mill for immediate delivery and hired an aspiring machinist, engineering interns, and an accountant.

With a mill in his garage, and four people working in his house, his team began a search for CAM software, contacting vendors, and spending a full week evaluating three packages. While one was considered the most popular, McCune was highly interested in another because, being embedded, it was touted as being fully integrated with his CAD system. The third, GibbsCAM, had been Jungst’s standard for 20 years. The single goal, he emphasized to vendors, was making a very difficult part and nothing else. “Put your best programmer on it. We’ll cut the part. If your software does what we want, we’ll buy it,” he told them.

All three vendors wanted the business, but two tried to coach the group by telephone. According to McCune their guidance amounted to “You can do it, if you know how.” McCune explains: “In contrast, the GibbsCAM Reseller, took our urgency seriously. He lives in an other, distant part of the country, but he came, and sat with us in my living room, to program the part while showing us what the software could do. He spent a few days with us.”

Vendor effort aside, the full integration of the first package tempted McCune, who quickly found the number of mouse clicks required to get anything done to be excessive. “The integration was more visual than functional,” he says. “The other packages weren’t embedded, but they didn’t require a lot of steps or remodeling the part. I was attracted by GibbsCAM’s clean interface and the few mouse clicks it required. It was efficient, people seemed to pick up on it quickly, and our GibbsCAM Reseller and Gibbs demonstrated terrific support, helping us to figure out this part.”

McCune describes the part as fitting within a 0.750" (19-mm) cube, extremely complex, with deep channels and irregularly shaped pockets throughout, some intersecting at complex angles, and most requiring surface machining. In production, such a part would be die cast, but as a prototype, it required machining, because other prototyping methods couldn’t produce the part with the critical tolerances and strength required.

For example, he finds that for all the excitement generated by 3-D printing, it isn’t ready to replace machining for functional prototypes. “It has its place, but has limited ability to provide a part that can be tested and manufactured,” he says. “The industry has done a disservice to education, leading students to believe that, with a CAD model and 3-D printing, they can manufacture. When I see students of design engineering proudly display a printed part or assembly, I often think, ‘That’s only 10% done, because manufacturability, material and functioning part haven’t been considered.’”

Working with tiny end mills, machining began. “We were dumb,” says McCune, “but that proved advantageous. Not knowing any better, we did things you just don’t do, things sane people won’t do, because we would spend a whole day replacing broken cutters.”

With small tools, some of 0.025" (0.64-mm) diameter extending to nearly 1" (25 mm), they broke a lot of tools, adjusted parameters, broke more tools, made more adjustments, but learned a lot. “Finally, there we were, holding a part for the customer, with a complete and successful machining process we could manipulate, change, and reprogram,” McCune says. “We had learned how to make a part that experienced machine shops said couldn’t be machined.”

Throughout the trial, McCune became impressed with GibbsCAM. Whenever different parameters, tool motion, machining pattern, entries, or exits were needed, GibbsCAM easily accommodated them. “We put GibbsCAM to the test, the machine to the test, the machinists to the test. Everything was tested, and we delivered the part.”

With a proven process, the parts went through dozens of revisions, and the group prototyped hundreds of parts, without the pain of many broken tools, and with a profit. Success and confidence led to more clients and more equipment. In 2006, the group was incorporated as Autopilot, specializing in product design and development. In 2007, having outgrown all available space in McCune’s shed, garage, and living room, Autopilot purchased a building. Within 18 months, the company had 15 employees, three Super Mini Mills, a TL-1 lathe, and SL-10 turning center from Haas Automation (Oxnard, CA), plus necessary support equipment and three seats of SolidWorks and GibbsCAM.

According to McCune, SolidWorks, GibbsCAM and CNCs enabled the company to grow like no other prototyping methods could have, allowing Autopilot to take projects from mere concept or napkin sketches, through design, development, and prototype, and even some production work to keep machines busy.

Today, Autopilot has over 200 clients, from very large companies to individual inventors, and is contractually unable to disclose most of their work. A project they can discuss, to a limited degree, is a family of drill bits they are taking through various iterations for a medical client, who tests them between iterations. Machinist and NC programmer Tim Robison turns the round features on 17-4 stainless steel blanks, before parts are sent out for cannulation. Then, on a Super Mini Mill and 5C indexer, he machines three flats on one end, flips the parts, and machines the flutes to completion in four-axis. Deburring, polishing, passivation, and engraving complete secondary operations.

To pursue medical prototyping and production, an interest generated from serving medical clients, Autopilot is very close to achieving ISO 13485 certification. Although not part of McCune’s original plan, the economy drove Autopilot into production as a cushion for survival, with the company once doing a part run of 250,000 pieces.

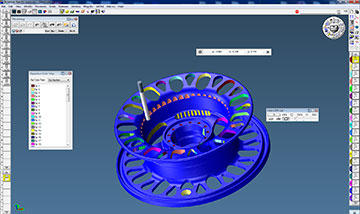

One project, a combination of prototype and production, allowed the creation of a local company, Bozeman Reel, when, relying on local fishing guides and fly fishing enthusiasts for consulting and testing, Autopilot took on the design and prototype of three lines of fishing reels, which Autopilot also machines and assembles.

McCune says that Autopilot’s goal is to become a world-class design, development and manufacturing company, in Bozeman, and believes the experience and confidence gained by employees provide solid footing to get there, while providing employment for people who share a sense of adventure, design, and manufacturing, with time, of course, to enjoy the great Montana outdoors. To continue growth, and do more production, he believes Autopilot will need CNCs with larger work envelopes, and perhaps a multispindle, multiaxis machine. “It will be interesting to see how GibbsCAM will get those programmed.”

As seen in Manufacturing Engineering

Capristo Automotive has set itself the goal of enhancing luxury sports cars with high-quality accessories and making them even more unique. GibbsCAM was brought on board when the CAM programming of an INDEX G400 YB could not be managed with the existing CAM software.

Northern Maine Community College (NMCC) has implemented a curriculum that equips students with CNC programming skills using GibbsCAM software, allowing students to earn certification within 9 months and achieve a 100% employment rate.

MUT-Tschamber, a mechanical engineering company in Germany, has implemented Sandvik Coromant's PrimeTurning™ technology and GibbsCAM NC programming solution to achieve higher throughput and productivity.

Toolmaker Rieco System Srl achieves greater machining precision and optimized production time with the help of GibbsCAM software.

SAFA GmbH & Co.KG specializes in the machining of non-ferrous metals, particularly brass, and has developed expertise in machining electrode copper for the production of plug contacts for electric vehicles.

Swedish metalworking company AB Larsson & Kjellberg has embraced 6-axis digital CAM, using GibbsCAM software, to efficiently process production parts for a wider base of customers using their Soraluce FR-12000 milling machine.