Same location for 90 Years. That’s what Kevin Binkert would like as a tag line for his company, Standard Metal Products (SMP), in San Francisco, California. Why? To signal the company’s humorous christening and unorthodox beginning.

The name came from a plaque Binkert found in early 1993, in the warehouse he had just leased. He loved the 1920s look of the plaque, and was attracted to the name because he could “make just about anything” under that banner, which is precisely what he wanted, as long as the jobs would challenge and teach him, capture his interest, and keep him on his toes.

He had no career plan when he entered the University of California in Santa Barbara, where he worked toward a degree in Sociology and studied art, computer science, engineering, and other courses outside the curriculum

Intrigued by Arty Mechanical Things

Loving to solve technical problems, Binkert started working with a machine arts group to produce mechanical contraptions that had no purpose other than challenge the creators, and amaze audiences at art festivals and large-scale robotics exhibitions. At Survival Research Labs, self-described as “producing the most dangerous shows on earth,” Binkert discovered that machine arts was what he really wanted to do. After a few years with the group, he struck out on his own.

Starting on a shoe string at his refurbished warehouse, Binkert purchased economical, well-made equipment, doing whatever he could to keep the lights on.

Affordable Equipment to Start

“The timing was fortunate,” he says, “because the government was closing military bases everywhere. The many closures in the Bay Area simultaneously hurt the local economy and enabled me to find good, affordable equipment."

He purchased some equipment from Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard by waiting for auction’s end to purchase remaining equipment. “I was buying quality machinery by the pound,” says Binkert.

Binkert took on prototype and short-run production work, while continuing to learn all he could from machinists and other craftsmen as he researched and acquired additional equipment. in 1998 SMP purchased its first CNC, an Okuma 3VA, a 3-axis mill that “came with a machinist who knew NC programming,” Binkert says. “He had been with that ma-chine for years and I hired him. He became my instructor in NC programming, and was a most valuable trainer because he taught me to visualize tools moving through the work piece, instead of visualizing work piece motion.”

The Okuma widened SMP's market and reduced costs and lead time. Adding a rotary table to the Okuma added a fourth axis. Then, in 2001, SMP purchased a Mori Seiki CL25 CNC lathe. The incremental capabilities, despite manual programming, further reduced cost and lead times, and extended the shop’s ability to compete, increasing its prototype and production work.

GibbsCAM Solved First Challenge

Birkert's first experience with CAM cam when challenged with making 40 Gorter valves, (assemblies of 12 machined components), for the San Francisco Fire Department. It was not something he wanted to attempt with manual programming. Working with a friend, a GibbsCAM user, they programmed the various components, some made from raw stock, while others from castings.

“Without the software, the job would have taken forever,” Binkert explains. “The threads on the valve bodies were especially challenging, but GibbsCAM has a thread milling function, which allows cleaning a bore and threading it in a single set up.”

For the four holes, they used both multi-tooth and single-point threading inserts. Because these provide a reduced and constant load on the tool, the finish was smoother. Binkery discovered additional advantages to milling threads. He could use a sin-gle tool for different hole diameters, which ranged from 1.5” D to 3.5” D, and when threading was done, he could mill the required higby on the start thread on the same set up, to provide a positie start, without cross threading, when firemen need quick connections to hose and hydrant. The rest of the parts, including the machined valves and turned worm gear, valves and caps presented little challenge for the software and CNCs.

Discovered by the Discovery Channel

In 2007, the Discovery Channel asked Binkert to join the Prototype This! television show. He worked on nearly every

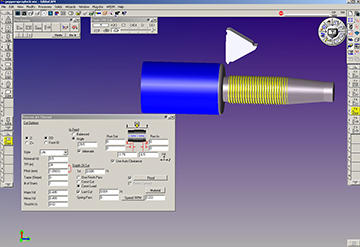

build and designed and built a "traffic busting truck". With transformer-like hydraulic legs and omnidirectional wheels, it could drive and park over other cars. “That year was revolutionary for us,” says Binkert. He leased an Omax 55100 Waterjet and, recalling his prior experience with CAM, he acquired the GibbsCAM Lathe and Mill modules, now choosing the software for its popularity, which would allow him to find programmers as needed, and for its flexibility in providing multiple methods to machine parts.

Binkert says that GibbsCAM and the waterjet made him immediately more capable and competitive. “As a bonus, I discovered that the software was easy to learn and use, and during my training at Gibbs, I was pleased by the accessibility of the people, including Bill Gibbs,” he adds. “They were fast at getting me post processors for my machines, and their service is great. They really care about their customers.”

Binkert says that machining services require trust and credibility.

If you are known for having tools of the highest quality, it helps build trust. He finds that job shop customers want everything made yesterday, and claims that GibbsCAM has helped him turn jobs around quickly, in part for its ability to work directly from multiple CAD formats.

GibbsCAM Helped Build Trust

“GibbsCAM is fast and powerful. If I make a mistake, I edit graphically, which is much easier, much faster, and more reliable. Furthermore, with GibbsCAM’s integrated Cut Part Rendering, I can verify every toolpath before I start cutting.”

The individual parts for the traffic busting truck were fairly simple, but the assembly was quite complicated and was built at SMP in only 3 weeks. By modeling with SolidWorks, and programming everything with GibbsCAM, Binkert achieved quick turn-around. The "traffic busting truck" was a success, and the build aired in October of last year. SMP now makes parts for Mythbusters and continues working for Prototype This!, machining parts for nearly every build, including some that never aired.

“This includes a lot of waterjet parts,” explains Binkert. "I often use the waterjet to profile parts before machining, because it saves a lot of time roughing. I found I can cut any material, including hard metals over 4 inches thick.”

The Omax waterjet had provided great productivity and many opportunities, so when the equipment lease expired, Binkery bought the machine. In January, he sold the Okuma 3VA and purchased a more capable Okuma MX-45Vae, now equipped with the earlier machine’s rotary table.

Binkery appreciates the value and profit of production work, but prefers the balance of diverse projects. With his two employees, additional contract employees (when needed), and an assortment of vintage to modern tools, his ideal operation is one where one or two machine tools are running production while he works on a prototype, a clock or a machine-art mechanism in another part of his shop.

That ideal is achieved often, as Standard Metal Products machines parts for various prototypes, trains, buses, the San Fransisco Exploratorium, the Stanford Linear Accelerator, the biotech industry, parts for water treatment, and components for the Stanford University and Oakland Tribune clocks which SMP restored and maintains. The company will soon begin redesigning and making parts for sculptor Maya Lin’s granite water clock at Stanford.

While crediting GibbsCAM and his CNCs for his increasing success he believes his diversity will keep SMP busy, even through the worst economy. Kevin Binkert hopes to show young people what manufacturing and technology is all about, that making things is cool and to inspire the next generation to bring manufacturing back to this country.